~No intelligent excuse can be offered for the senseless slaughter and awful waste of a valuable and harmless animal purely for personal gain or to satisfy a blood-lust to kill. -Martin S. Garretson

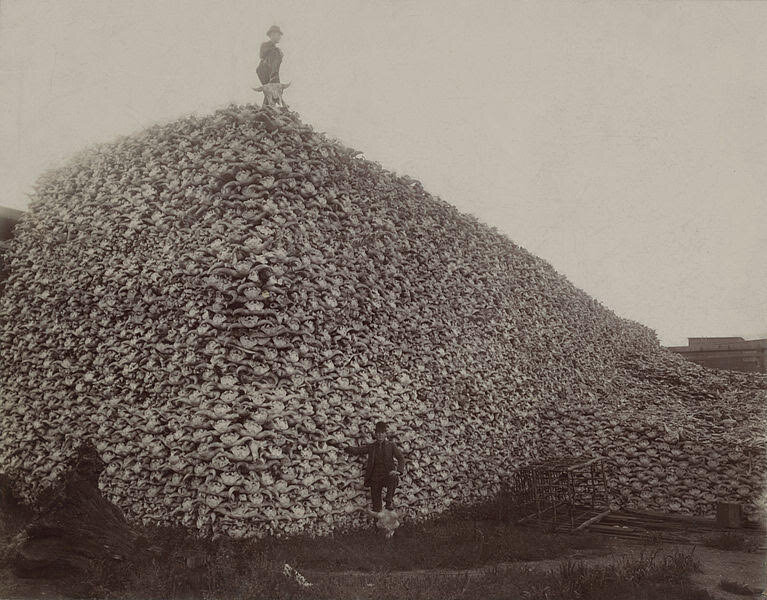

80 million bison once roamed our prairies. The near extermination of the American buffalo did not happen overnight, nor was one generation of human fully responsible. Collectively, Native American Indians and white men increased the momentum. During the 1800s, approximately 200,000 buffalo were killed annually on the plains for trade of their hides, and tongue alone. For centuries, the remains of the discarded bison bones and meat left behind had slowly bleached away, decompose and became nature’s complex system of recycling life’s basic chemicals for grass.

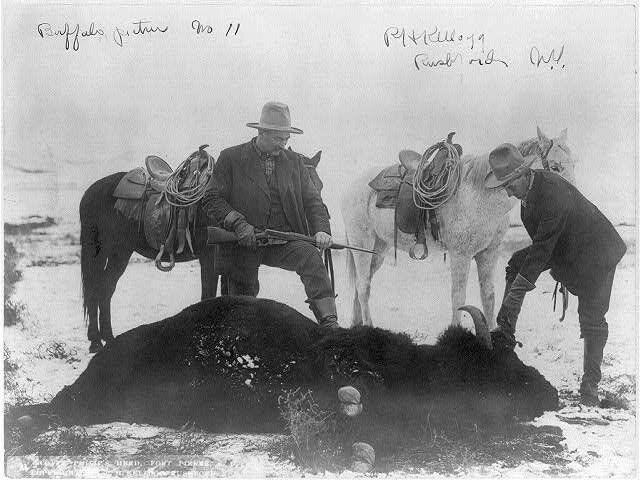

In the mid 1870s, during the peak of the buffalo slaughter in western Kansas, a buffalo hide yard would handle as many as 80,000 hides at one time. Trade became so abundant that hides were often sold for $3 each by the hunter to wholesale dealers who then turned around and sold the hides anywhere from $8.50-$16.50 for low to high quality robes.

When the American exploration of the prairies began, the vast numbers of how many buffalo were encountered made it difficult to imagine that such killing would do great harm to the species. Not until 1864, was interest shown to pass laws attempting to protect wildlife, like the buffalo. Idaho Territory became the only one, state, territory or federal to pass legislation making it illegal to hunt buffalo between February 1st and July 1st, however all other times, it was open season and buffalo were already few and far between consisting of mostly the mountain variety in areas rarely reached by man. Slaughter had already taken its toll.

Once Idaho legislation passed, other lawmakers in Washington, began taking note of the thousands of accounts told of needless bison slaughter for hides. Congressman R.C. McCormick, Territorial Delegate from Arizona, introduced a bill aimed at reducing the slaughter, which read:

That, excepting for the purpose of using the meat for food or preserving the skin, it shall be unlawful for any person to kill the bison or buffalo found anywhere upon the public lands of the United States; and for violation of this law the offender shall, upon conviction before any court or competent jurisdiction, be liable to a fine of $100 for each animal killed.

Ultimately, the bill failed, having never been reported back from committee to the House of Representatives for action. However, over the next two years, Wyoming and Montana legislature passed similar laws to that of Idaho, aimed at reducing the killing of buffalo. Meanwhile, in Kansas, where perhaps the grossest of negligence of the senseless killing of bison still occurred, protests arose warning of the animals possible extermination. Congressman McCormick renewed his appeal to protect the buffalo referring to the buffalo as “the finest wild animal of our hemisphere.” He then, in hopes of strengthening his case of appeal, read several letters that had been written by army officers who had served on the buffalo plains of Kansas and Nebraska expressing their indignation that such cruelty to wild animals should be allowed to continue.

Had McCormick stopped at this point with the cruelty to wild animals, he may have been successful in some sort of further legislative protection for the bison, however Congress took no action to further protect the mammal when McCormick went on to further read a letter written by an Indian Agent and respected army officer citing the remarks of a Cheyenne chief, “Little Robe” who had once been scolded by the agent for allowing his young men to kill a white man’s ox. The Chief chided, “You people make a big talk, and sometimes war, if an Indian kills a white man’s ox to keep his wife and children from starving. What do you think my people ought to say and do when they themselves see their cattle (ie: buffalo) killed by your race when they are not hungry?”

The truth hurt. Congress members were reminded that the buffalo was the Indian’s commissary and that if the Indians continued to have buffalo, they would prove to be most difficult to control.

It wasn’t until closer to the 1900s that slaughter of the buffalo nearly caused extinction. It was the help of one white man and an Indian of the Flathead reservation who saved the buffalo. For $2,000 in gold, the set price for thirteen buffalo, a man by the name of Michel Pablo set out to increase the herd by seeking to raising buffalo. By 1906, the herd numbered about 300 and Pablo sought out the federal government by asking President Theodore Roosevelt to trade him land on the Flathead reservation. Congress refused to appropriate the money for the buffalo causing Pablo to approach the Canadian government for grazing land for he and his herd. Instead of offering Pablo land in exchange, they negotiated the price of $200 a buffalo ultimately removing the buffalo from United States soil.

In the past 140 years, with the valiant efforts of some and a crusade that never fully left the mind of President Theodore Roosevelt, more and more began to point out the concern of the vanishing buffalo causing a handful of ranchers, working independently across the west, to hang up their rifles to help save the bison. A group of like-minded individuals set forth to form a society to work towards the permanent preservation of the buffalo. The American Bison Society then began to work towards establishing federal buffalo ranges, like the one at Yellowstone, along with memberships which enabled the society to raise adequate funds for its work. Within 2 years, Congress, having felt embarrassed by the Canadian purchase of Pablo’s herd rather than their own, appropriated enough money to purchase land for a buffalo refuge in western Montana. In 1909, the new range was fenced and buffalo purchased from independent ranchers were bought across Flathead and brought to their new home with a total of 158 buffalo. A year later, the total number had increased not only naturally but were “gifted” further bison in support of the extreme efforts spent to save the mammal from extinction. To this day, independent bison ranchers are still the crossroads between conservation and commerce. Critical to efforts set forth in saving both the landscape and the species, each rancher who engages in the mission of restoration does it for the pure unbridled love of the American Bison.

*Information noted above was taken from the excerpts of, ‘The Buffalo Book, a full saga of the American animal’, written in 1974 by David A. Dary